Old Data Leads to New Discovery About Uranus

Ten years after the Voyager 2 spacecraft launched, it reached the mysterious hazy pale blue planet, Uranus. The data collected was interesting but didn’t surprise scientists until recently, when a new look at the old data resulted in a groundbreaking discovery — a plasmoid.

August 20, 1977, marked a new era in space exploration when NASA launched the Voyager 2 mission to explore the outer reaches of the solar system. Voyager 2 promised the first opportunity for close-range study of the four Jovian planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and their moons. Data and pictures captured during the first years of the mission, with a flyby of Jupiter of 1979 and Saturn in 1981, thrilled scientists and the public alike.

Uranus did not generate the same excitement at the time. However, the new study by Gina DiBraccio and Daniel Gershman, Voyager 2 Constraints on Plasmoid-Based Transport to Uranus, found something new. A pocket of energy was slowly leaching mass away from the planet.

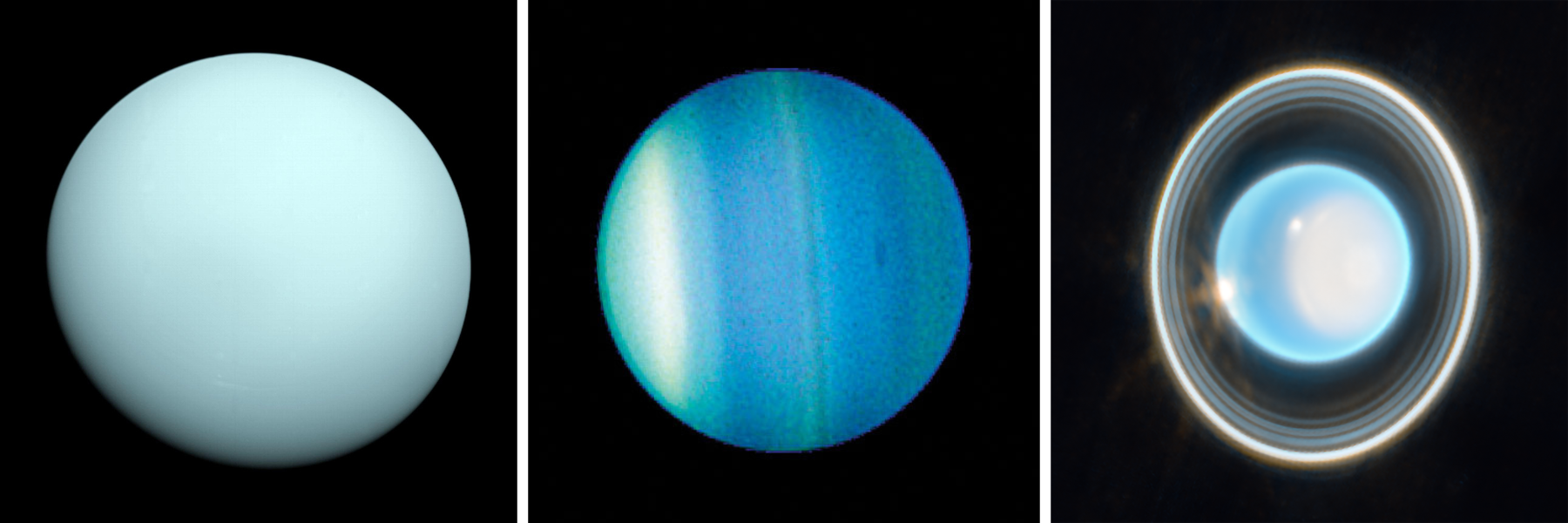

(left) First photo of Uranus ever taken by Voyager 2, (center) Uranus photo taken by Hubble Space Telescope, (right) Uranus photo taken by the James Webb Space Telescope.

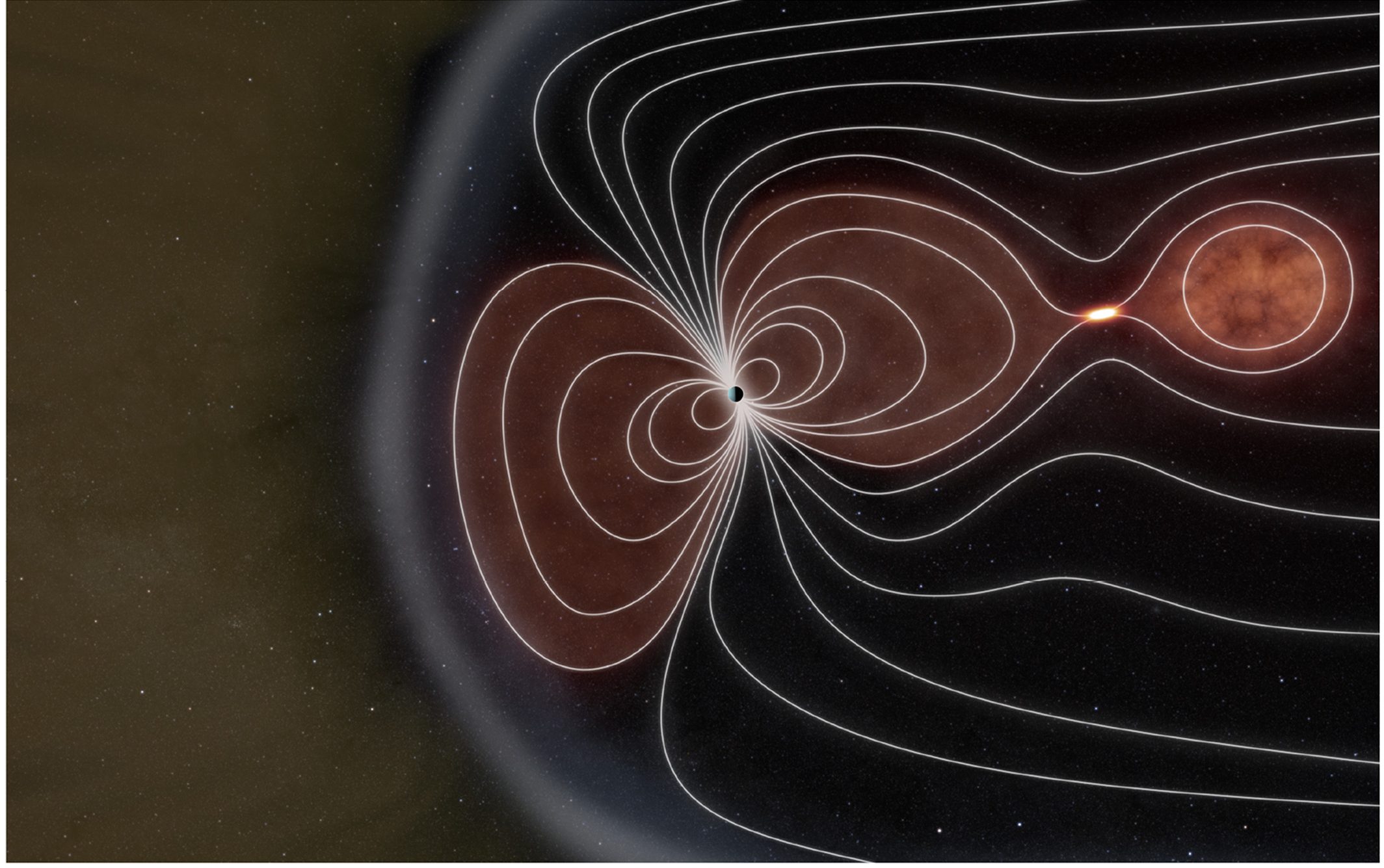

To understand these new findings, we first need to explain magnetic fields. A magnetic field is an invisible force that encircles a planet and creates a protective barrier from hazards like the solar wind. The solar wind is a steady stream of charged particles thrown out from the Sun. When these particles interact with a planet’s magnetic field, a planetary magnetosphere is formed. The stronger the magnetosphere, the more a planet is protected. One example of a planet with a weak magnetosphere is Mars, which is dry and desolate, because over millions of years the magnetosphere has weakened and eroded away leaving the surface vulnerable to hazards.

The magnetic field can be imagined like a large bubble made of invisible lines that loop around the poles. Sometimes these lines can be broken and can reattach in the wrong place, forming a pocket. Over time, solar wind particles get trapped inside the pocket, creating what is known as a plasmoid. Astronomers and other scientists have identified plasmoids on all of the planets except Uranus and Neptune, until now.

Depiction of Uranus’ magnetosphere with a plasmoid from the article.

The seventh planet from the sun, Uranus, is one of the two ice giants. It is four times larger than Earth and is made entirely of frozen gas. Like Saturn, Uranus has rings, but instead of circling the planet like a giant hula hoop around the middle, the narrow rings circle from top to bottom. Uranus is the only planet in our solar system that is tilted sideways, potentially the result of a collision with a planet-like object long ago. Its equator is at a right angle to its orbit.

With its extreme distance from the Sun and sideways tilt, scientists did not think Uranus could develop a plasmoid. Using what we now know now as a guide, DiBraccio and Gershman took a new look at the original data from Voyager 2 and confirmed the spacecraft had flown through a cylinder loop-shaped plasmoid. This eccentric shape is believed to be caused by Uranus’ bizarre rotation.

Constantly exposed to the force of the solar wind, these plasma structures break, sending the accumulated matter and charged particles deeper into space. The loose strings of the magnetic field eventually reattach, forming a new pocket, and the cycle continues.

Despite Uranus’ size, this process of buildup and release will slowly strip away the planet’s mass. Using Voyager 2 data, DiBraccio and Gershman found Uranus is losing mass faster than Jupiter and Saturn, even though they are bigger planets and closer to the Sun. How is that possible? The two authors concluded there must be some other unknown force keeping Uranus from losing its material too quickly.

Most scientific discoveries prompt more questions than answers. Scientists study the solar system because it helps us better understand how the universe works. DiBraccio and Gershman were able to prove one plasmoid event happened on Uranus, but we don’t know when magnetic field lines break, how often plasmoids form or last, the real speed of Uranus’ mass loss, and what keeps the magnetosphere strong on Uranus. Until we can revisit this part of the solar system, these questions will be left unanswered.

Eugene and Springfield Have a Poop Problem

Aging infrastructure and new environmental standards are driving upgrades to wastewater

facilities that could benefit residents

The Metropolitan Wastewater Management Commission is preparing to approve a new 20-year Comprehensive Facilities Plan that includes major upgrades to Eugene and Springfield’s aging wastewater treatment infrastructure, including the biosolids management facility.

“There are three options you can do with biosolids material: you can use it as fertilizer, you can haul it off and put it in a landfill, or you can incinerate it,” said Michelle Miranda, city of Eugene’s Wastewater Division director. “We produce anywhere from 2,000 to 6,000 tons per day. That’s a lot.”

The commission oversees wastewater collection and treatment for Eugene, Springfield and parts of Lane County. At the MWMC Oct. 10 meeting, staff presented the finalized draft of the Comprehensive Facilities Plan. This document outlines upgrades to the Eugene-Springfield Water Pollution Control Facility through 2045. The plan is scheduled for final commission approval in March 2026.

“This process facilities plan is the story of an aging facility,” said Bryan Robinson, an environmental management analyst for MWMC. “It’s not past its prime, but it is 50 years old and needs some work and needs some more study to continue to operate at the high level performance that it has.”

The biosolids management facility plays a key role in wastewater treatment. Poop and other solids are removed from wastewater and pumped into lagoons, where natural decomposition stabilizes the material before it is treated and dried into biosolids.

For the past 30 years, the Eugene-Springfield facility has converted biosolids into fertilizer sold to local grass seed farmers. However, fluorinated hydrocarbons, also known as PFAS, are disrupting this relationship. PFAS, or forever chemicals, are not currently removed during treatment and can be found in water, air, fish, soil and the blood of animals and humans. Linked to health and environmental risks, they are widely used in heat-resistant materials, water-resistant clothing and cosmetics, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

PFAS contamination has prompted growing concern among Oregon farmers, who worry the chemicals could make soil less productive over time. The problem is that biosolids keep getting made, and there is nowhere productive to send them.

“We’re seeing process issues with soil handling,” Miranda said. “We produce solids as part of the treatment process, but we’re less efficient in being able to treat them. So that’s why it’s the pinch point.”

The treatment plant, located off Randy Pape Beltline and River Road, along with the 49 pump stations across Eugene and Springfield, cleans an average of 35 million gallons of wastewater every day, serving a population of more than 280,000 people. That’s the equivalent of 53 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water.

The previous Comprehensive Facilities Plan, approved in 2004, focused on increasing treatment capacity. The new 2025 plan assesses the plant’s existing infrastructure and identifies ways to improve efficiency and integrate new technology.

The new plan includes 25 recommended projects in the Capital Improvements Plan, with a combined cost of $253.9 million. All projects fall into three main categories: existing conditions, regulatory drivers, and flow and load projections.

“A number of these projects are projected to lower operating costs over electricity use and chemical use,” said James McClendon, Eugene wastewater finance manager. “So even though they have an expensive upfront cost, they’re cheaper in the long run.”

Nine of the 25 projects are study-based recommendations, totaling an estimated $3.39 million. The top three priorities are repairing clarifiers and final treatment systems, conducting a biosolids improvement study, and upgrading the WPCF (water pollution control facility) boiler. These three initiatives have already received funding. However, inclusion in the plan does not guarantee implementation within the 20-year time frame.

During the meeting, Commissioner Christopher Hazen expressed concern about the impact of the Capital Improvement Plan’s costs on taxpayers. MWMC Executive Officer Matt Stouder responded, “We’ll have to do some looking. There will most likely be a fee increase in the next 10 years. But we won’t know yet.”

The final Comprehensive Facilities Plan is scheduled for presentation at the MWMC meeting on April 10, 2026.

“There’s a lot of planning work,” said Todd Miller, City of Springfield environmental services deputy director, during the meeting. “Having that consistent broader consideration for the community will help MWMC make the best possible decision for the repairs. And that’s where an integrated plan will come in and help guide us.”